The last two weeks have been challenging; I’ve been sidelined by excruciating, mysterious nerve pain. It’s dental, on the right side of my mouth, between my gumline and palette. Despite this, when the pain has subsided to a headache, I’d resume my relentless job search instead of resting. The remainder of my time has been spent attempting to catch up on reading or struggling through homework assignments for a course in AI Product Design I’m in. I haven’t been able to write. As you can imagine, the results of my attempts have been subpar, not even close to half-assed. I’ve had to abandon my homework. My best is nowhere in reach, but even with the tempting idea of rewatching Arcane, I couldn’t stand wasting my days on Netflix. Going to bed felt like giving up.

I realize now that the anxiety of joblessness, combined with chronic pain, has led to some poor decision-making. So, on Saturday, I finally allowed myself to rest and relax. I took some effective painkillers and slept most of the day. During wakeful moments, I indulged in brief journal entries and tinkered with Procreate, an app on my iPad that I’ve neglected for years. I searched Kindle for the guides I’d purchased long ago to learn how to use its simple interface and hidden gestures. While this may not sound like resting, to me, it felt like playful exploration—a luxury I hadn’t allowed myself in too long. Holding that sleek, sexy Apple Pencil, I felt a rare delight bloom in my heart.

I have several Art Instruction Inc. course books from the 1960s, which I permanently ‘borrowed’ from my dad during high school after several failed attempts in my younger years. My dad always discovered they were missing and asked for them back. The books are slim; most are about 30 pages each and oversized, like paperback coffee table books: 13 1/2” x 10”. Toddler scribbles mark some—my own—they’ve always been a cherished part of my childhood. I don’t remember being punished for those scribbles. Considering my dad’s impatience and always present rage, that could be regarded as a minor miracle, but I rarely got in trouble for anything related to drawing. Aside from that one time, I wrote the alphabet in purple crayon along the lower part of a coat closet wall. Actually, I covered all three walls. I ensured that the letters were spaced out evenly so that the alphabet stretched nicely across all three walls just above the baseboard. Purple was my least favorite color, and I knew it would take a lot of crayon because of the textured surface. I picked the coat closet, believing no one would notice. Although I knew it was wrong, the thought of having such a large canvas—a whole white wall—was too tempting. I selected the alphabet, convincing myself that my punishment would be lighter if I got caught. It was the sensation I craved, as well as the big canvas. I made quite a few calculated compromises with myself to make that decision. It wasn’t discovered until many years later when we moved out of that apartment. My mom didn't think it was much of a transgression and was pretty lenient: she handed me a sponge and Windex and told me to clean it. Totally. Worth. It.

I’ve always loved drawing and sketching, and my dad was supportive and encouraging; I was following in his footsteps. When I was tiny, he’d spent a lot of time teaching me perspective, line quality, and shading techniques. It never occurred to me then that he had learned these skills from the very course books I treasured. He talked about his talent like he was born with it. His ability to draw photo-realistically seemed like magic, and he never discouraged me from believing that. I remember sitting with him at the kitchen table, our fingertips covered in silver pencil dust, a thin film that made our fingers look like tiny antique mirrors. He showed me how to create a smooth gradient by rubbing the paper with my finger, barely touching the pencil line, and smudging the lead gently to create a shadow. When I tried this technique later, my art teacher discouraged its usage, saying it was a lazy cheat.

When I was seven, I was seduced by the ‘Draw Your Favorite!’ ad found in every comic book in the late ‘70s/early ‘80s. The idea of over $5000 in prizes seemed like an easy way to make a lot of money. I mean, the illustration was so simple. I drew all the characters, Tippy the Turtle, The Pirate, and Tiny the Mouse, hoping to impress the judges. The drawings took no time. It took longer to convince my mom to give me an envelope and stamp. I thought I was entering a contest with cash prizes, not putting my name on a mailing list for Art Instruction Inc. of Minneapolis, where the prizes were ‘scholarships.’ However, a salesman told my dad over the phone that I had won the only cash award, $25. I remember my dad standing in our kitchen, his curly black hair longish in that seventies style where the sides puffed out, disproportionate to the length on the top—too long to be clean-cut but not quite hippy length. He kept his mustache trimmed short. One hand is on the wood paneling, facing the yellow phone mounted there and looking at the floor. He’s wearing a short-sleeved blue work shirt with clear machinist’s oil stains, a bright white t-shirt that peeks up between his collar, and dark navy cotton pants. His security badge is attached to his shirt pocket. I imagine him wearing brown Hushpuppies. Did he own Hushpuppies?

“No, my daughter will not take the drawing course, Phil…”

(Sigh.)

“Because she’s seven, Phil...”

He turned and leaned against the wall, one hand between his butt and the wall, looking up at the popcorn ceiling.

”Yes, we know how talented she is, Phil.” Pinching the bridge of his nose with his thumb and index finger, the nosepiece of his eyeglasses balanced on his fingers. He squints his eyes. “But like I said, she’s SEVEN YEARS OLD.”

I stood about four feet away, clutching my hands together, listening to every word. I thought I was watching my dad kill my dreams. I imagined dropping out of elementary school and attending ART SCHOOL. I wanted my $25; that was more than enough money to run away and begin my art career. I stomped around the house and pouted for days. I had no idea how unrealistic any of this was. Also, I hadn’t read any of the text below, “Draw Your Favorite!” I didn’t care about any of the details.

I never put together this connection, and I now wonder if that’s how my dad found the course. He, of course, never said a word about it.

When I was in the first grade, I started biting my fingernails. My mom tried everything to get me to stop, but the compulsion was too strong. She even tried dipping my fingers in red chile powder as a deterrent, but I’d wipe most of it off; the taste of what was left made the experience even more enjoyable. I was leaving evidence of orange-powdered fingerprints everywhere. She caught me mid-lick, causing her to start screaming at me in pure frustration, “If you don’t stop, I’m taking away all your drawing supplies.” Already paralyzed with fear (busted!), my index finger touching my tongue, I dropped my hand and talked back, “NO,” I said. My eyes were wide and watering, not from the chile but from the idea of being grounded from drawing. Realizing her sheer genius, a new, more effective threat of punishment was born. My nailbiting ended immediately. I don’t have wounds of trauma from that particular, more civilized and effective punishment. I was more than happy to comply when it came to losing the one thing I truly enjoyed.

Medicated, energized, and excited, I was ready to start my Procreate instruction earnestly. I got out of bed, took those mid-century art guides off the bookshelf in my office, and headed to the living room. I laid back on the sectional, accompanied by two thrilled chihuahuas. It was freezing, and they were desperate for a warm snuggle, even with the fireplace roaring. I browsed the ‘Outline Drawing’ textbook for inspiration and cute, easy cartoons for my first Procreate lesson. I recognized some of my favorite characters, ones I’d drawn many times when I was a kid. I made a couple of mental bookmarks and began browsing the other textbooks. I’ve always enjoyed looking through them, and now it is easy to see how they’ve influenced my drawing style and how timeless these basic foundational skills are. The drawings are so vintage, and no black or brown people are used as subjects—no stereotypes and, thankfully, nothing worse.

Some course books are missing covers. One has a rusted staple that broke long ago, and the pages are coming loose. They have a specific aroma beyond musty, old paper. They smelled like my grandmother’s house.

We lived with my dad’s mother for about a year while I was in the sixth grade. She had reams of old typing paper, and boxes of this paper were stashed all over her house. The paper was very thin; one side had a strange, smooth texture. The paper was so old that the pages had a light brown vignette on the edges and a weird chemical fragrance, perhaps from the coating. When I asked her where she had gotten all that paper, she just shrugged and said that my uncle Frank had found it and never moved it out of her house. I vaguely remember other office items. My uncle Frank was an opportunist with lots of schemes running simultaneously. These were probably leftovers from a liquidated business he had intended to make a profit from. I speculated that when he didn’t find a buyer he abandoned them. When I asked if I could have the paper, like, all the paper, she shrugged again and walked away. I assumed possession and had a lot of drawing paper that year. I don’t know why the textbooks smelled the same.

I opened the Basic Figure Drawing book, and inside were two old envelopes addressed to my dad. I vaguely remembered papers in one of these books but hadn’t spent time looking at them. The envelopes were empty.

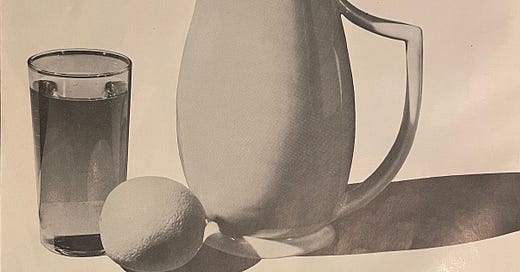

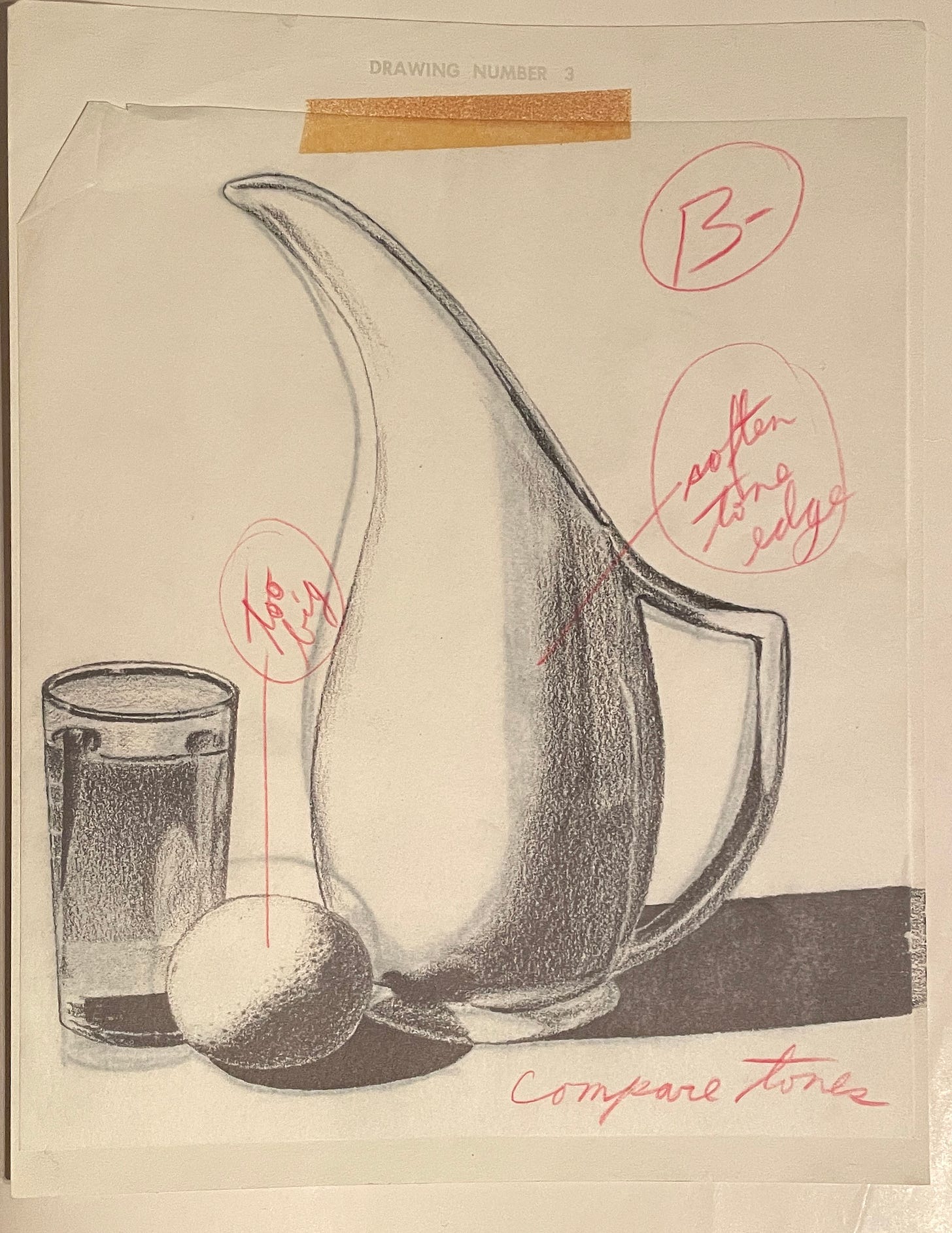

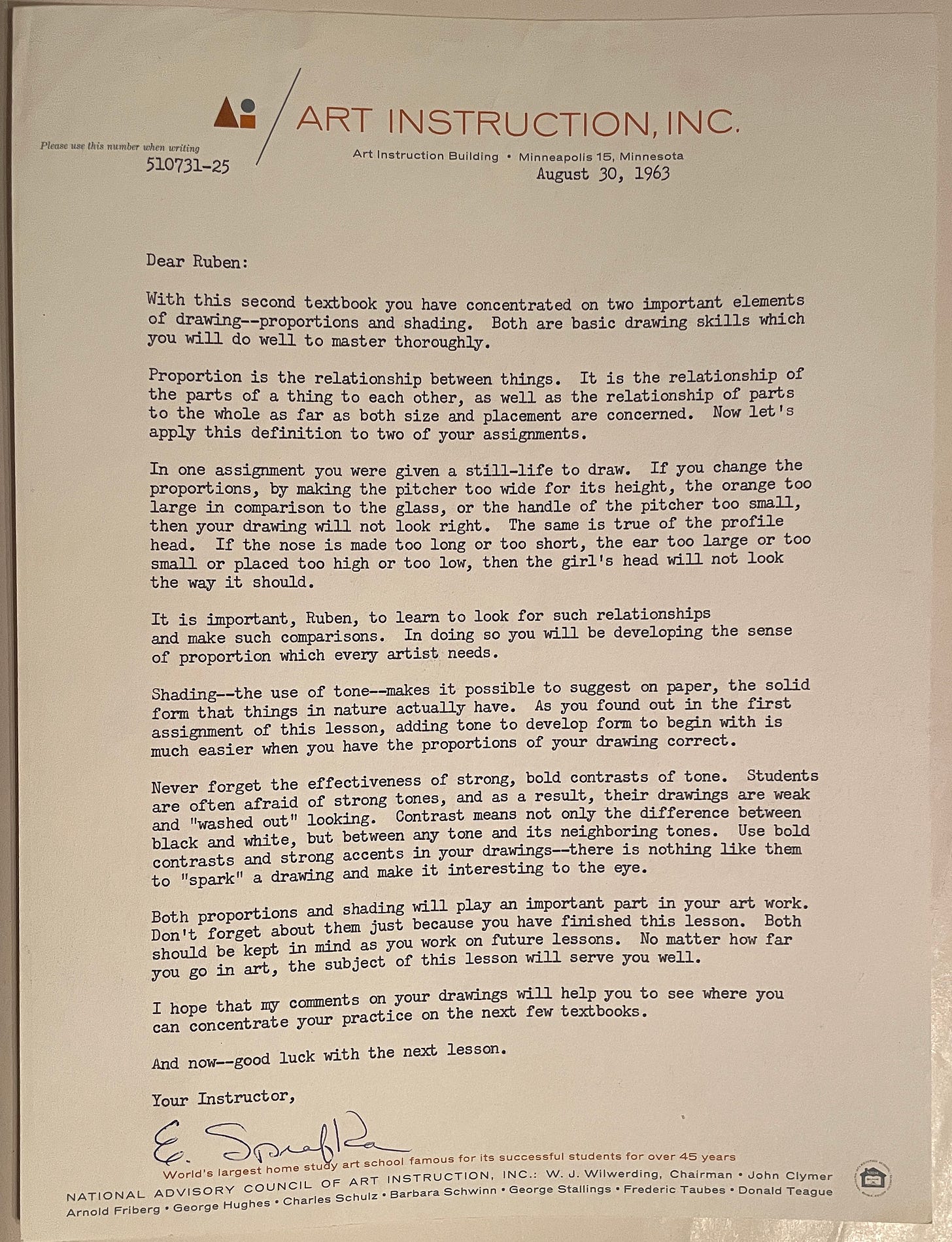

I flipped the page, and there was an 8 x 10 still-life drawing of a stylish ceramic water pitcher, a drinking glass with water in it, and an orange. At the top of the page was “DRAWING NUMBER 3,” printed in light gray Futura on heavy drawing stock. A yellowed piece of masking tape was directly beneath the label. Next was an almost vellum-like page with the same illustration, markups, and a grade, “B-” circled in red, with the mirrored and matching masking tape at the top and a typed letter behind that. Feedback. It was clever how the instructor used this method to compare the ‘correct’ way to draw the still life with an overlay. I remembered that the reference image was in another book, ‘Proportions and Shading,’ so I grabbed that and started comparing my dad’s drawing to the assigned photograph. Why hadn’t I ever looked at these before? I didn’t think the feedback in the letter was constructive. The instructor used overwrought language, peppering the letter with my dad’s name, trying to sound personal and not boilerplate. At first, I didn’t think the drawing was very good. Then I did the math—the letter was dated 1963; my dad was sixteen.

Ruben’s still life.

Instructor’s feedback and grade.

Procreate forgotten, I started thinking about my dad: he was sixteen. He took a home study correspondence course when he was sixteen! I tried to imagine what he was like at that age—considering the violence of his childhood. My grandfather, who was either absent for months at a time or beating the shit out of him for whatever reason. His mother was cruel and resentful and took her anger out on her kids. Where did he find the energy or inspiration to learn illustration? Where did he get the money for the course? Did he want to become a commercial illustrator? I wondered if this was around the time when his dad told him that if he wanted to be an artist, he ‘must be a fucking faggot.’ He told me he gave up drawing altogether after that particular viciousness. I wondered if that was when everything fell apart. He might have given up on life, too.

I knew he was in a violent street gang before he left for Vietnam. The story is that he was arrested after being involved in a shooting. He always lifts his pant leg when he tells this story and points to three scars. Two on his shin and one on his calf. “These are from before Vietnam,” he’d say, implying he didn’t get shot in the war. The judge gave him a choice between juvenile detention or early draft. He was nineteen. My heart cracked open deeper and more painfully. I’ve spent very little time considering my father’s hopes and dreams. Is there a parallel universe where he tells his dad to fuck off? In this universe, Alternate-Ruben embraced his talent and masculinity, overcame racism, and had a graphic design or architecture career.

Pursuing his dream could have changed everything. Maybe.

A painting created by my dad has been a constant presence in our lives, it moved with us from home to home. This oil on black velvet features a conquistador adorned with a heavy, decorative gilded frame. He is wearing a tall gold embossed helmet secured with a tight chin strap; his mustached face is lined and scruffy with gray stubble. It always occupied pride of place in our homes. Our family mythology suggested that we were direct descendants of these colonizers. I grew up imagining the man in the painting was a distant great-great-great-grandfather, noting his resemblance to my grandfather. Only in adulthood did I discover that the painting was a copy of a popular 1970s piece of home decor, which was a replica of a painting that may or may not have been a Rembrandt, The Man in the Gold Helmet. A testament to my father’s skill, it was indeed a very convincing replica. I wish I had that painting.

The Man with the Golden Helmet, oil on canvas circa 1650, Circle of Rembrandt (1606–1669).

When I was in the seventh grade, my dad started drawing again for pleasure. It was also a not-so-friendly competition with me as I began to get attention for my drawing skills. His talent and experience blew my immature artwork away. During the summer, we worked on murals for my karate school in-trade for lessons for me and my sister. In the entrance, he drew life-sized mirror images of our handsome martial arts instructor, high-kicking over the school logo, and airbrushed the mural using a combination of freehand and this cool liquid mask that he applied to the wall with a brush. It was a breathtaking resemblance that gave strong low-rider or sexy van art vibes. I drew a less-than-impressive version of a single high-kicking instructor in the room where we had our classes. He was also inspired to draw a Willie Nelson portrait from an album cover that year, creating a loving portrayal in pencil. He framed and hung it in the dining room.

My dad, now in his 70s, spends his days bedridden, watching YouTube, and smoking medical-grade cannabis. My mom has rearranged their home so that his hospital bed is now in the dining room, where that drawing of Willie Nelson used to hang. He’d been disabled for around twenty years now; he’d stopped going to work the day he got lost on the commute he’d made every business day for about a decade. He could no longer work as a machinist, which required high-level math, precision designing, and machining. He has several physical ailments due to the years of alcohol abuse, smoking, and obesity. Even though his condition includes debilitating chronic pain, his cognitive struggles are what depresses him the most. He was intelligent, creative, and talented.

In writing these essays, I’ve gained a new empathy for my father, a feeling I’ve not had before. I don’t forgive him; all the violence and trauma. His competitiveness with me was never friendly. I’ll never forget the day I called him after I got my first significant paycheck. I expected the reaction of a proud father; I was making more money as a designer than he ever did as a machinist. I’ve blocked out what he said, but it was cruel. His disability took away his life, but it also took away his violence. He’s no longer terrifying; he’s barely there and rarely lucid. I have been thinking about him a lot lately, and I wonder if his time on this planet is running out. He is very ill.

Over the years, working in corporate environments, I’ve forgotten my early love for making art. I only remembered one milestone day in the summer between the 3rd and 4th grades. I was tracing Sunday comic panels—a forbidden exercise. Tracing was cheating. My dad found the pictures and raved about how much I’d improved. It was also his favorite comic, Hagar the Horrible. Why hadn’t I shown them to him? They were so good! He was impressed and couldn’t stop talking about how talented I was. I had a future in Art! I was ashamed of the tracing; I didn’t admit it. Instead, I practiced harder, ensuring I was as good as the tracing made me appear. I attacked drawing with discipline, and I got really good. I attributed this lie as the reason I ended up a designer. Lamenting that I fell into a career for all the wrong reasons. I had forgotten about my passion for drawing and the joy it has always brought me since the first day I picked up a pencil and tried to draw like my dad.

Now, I mourn for my dad and empathize with all he’s endured. For the first time, I can recall the memories of him spending time with me in a sweet and kind way. Not only did I inherit an innate gift from him, but he also invested time in teaching me to draw, encouraging me, and providing the resources to develop my talent, even when finances were tight. I always had access to quality art supplies, many times lending me his tools when there wasn’t the ability to provide me with my own, a gift that opened doors—allowing me to escape my hometown and build a career.

And for that, I thank him.